No matter how much you plan, life can be unpredictable. Life on the internet — even more so. Few people know that better than Brian Lee, a 2011 graduate of DigiPen’s BS in Computer Science in Real-Time Interactive Simulation program.

“I’ve always been interested in both the technical and art side of games,” Lee says, “I just ended up specializing in the technical side of it and keeping the art side as a hobby.”

Today, Lee earns his living programming mobile games at the Seattle offices of King, makers of the mega-hit Candy Crush, where he works on titles like Battle Nations and Paradise Bay. Despite his contributions to those popular games, however, most folks actually know him best for that “hobby” art on the side, and it’s all thanks to the anarchic tides of the internet. Some of Lee’s hobby art, much of which emerged from his days as a DigiPen student, has inadvertently rocketed to viral “memedom” on multiple occasions, landing entries on the Know Your Meme website. It’s a phenomenon that continues to surprise him.

An avid video game and comics fan since he was a kid, Lee first started dabbling with comics on his own in high school with his web comic series Left & Right. Upon graduating in 2004, he decided to pursue computer engineering at a university in California. That same year, the seed for his first accidental viral hit was planted.

“I went to a lot of LAN parties and played Unreal Tournament, and we’d always have the text-to-speech turned on in the chat,” Lee says. Whenever he would get killed, Lee would reactively “keyboard spam,” leading the text-to-speech voice to read lines of robotic gibberish. “One time I keyboard spammed the word ‘tane,’ and the voice was like, ‘TANE!’”

Particularly amused by the robo-utterance, the word became Lee’s new muse. “I registered a domain name for Tane, did a little Flash animation, and put a song I made on it. And somehow it just became a dumping ground for little experimental Flash projects that I would work on.”

The project, tane.us, is a fusion of interactive Flash animation, music, and original art, and it quickly became a place for Lee to endlessly riff (in increasingly surreal ways) on the made-up word “Tane.” Visitors to the site plummet deeper and deeper into the cascading “Tane” pages, hunting for the correct action to complete on each screen and progress to the next one. The project would outlast Lee’s time at the California university’s computer engineering program, which he left upon realizing it wasn’t the right fit.

“I eventually thought of DigiPen,” Lee says, “which I knew about since I’d seen it a bunch reading Nintendo Power as a kid. I made the decision to go up to Redmond, and it ended up working out well for me.”

While studying computer science at DigiPen, Lee made use of his quirky website to implement and test out the new skills he was learning in his classes.

I saw one speedrun and thought it was a joke, but then I saw more and more, and went, ‘Oh, I guess people will speedrun anything.’”

“I definitely gained a lot of programming knowledge through class that applied directly back to Tane — flashier, more complicated Tane pages,” Lee says. Around that time, Lee also started to befriend KC Green, the artist behind the popular web comic Gunshow that would breed the famous “This is Fine” comic. Green and Lee began collaborating — Lee building Green’s Gunshow website and Green contributing art to Tane.

The bizarre world of Tane eventually caught on, becoming one of Lee’s first viral hits. The strangest manifestation of that popularity, according to Lee, were the speedrun videos people began uploading of themselves navigating through the labyrinthine site.

“That in particular surprised me,” Lee says. “I saw one speedrun and thought it was a joke, but then I saw more and more, and went, ‘Oh, I guess people will speedrun anything.’”

Meanwhile, Lee dived deeper and deeper into game programming. His sophomore DigiPen game Gear, a fast-paced platformer, became a multi-year project as he and his team continued to perfect it for competition entries. Lee took on the primary role of gameplay designer, but true to his varied interests, he also took on the role of Gear’s graphics programmer, primary artist, and music composer. Gear would eventually win the Indie Game Challenge grand prize in 2010, as well as an honorable mention at the Independent Games Festival that same year.

“The skills I learned making the game projects, just those team dynamics, the workload, and the work timeline, were very relevant to the things I’ve since experienced in the industry,” Lee says.

As Lee sharpened his technical skills at DigiPen, he also made a conscious effort to keep drawing. “Because of class schedules, I’d have a class at 10 a.m. and then a class at 2 p.m.,” Lee says, “so I’d have hours of down time to work on little personal projects.”

In 2008, one of those in-between class projects would birth Lee’s next inadvertent smash hit, an infinitely memed drawing from a fan-fiction comic he made called “BROTERSTORY” for a friend’s SakuraCon zine. The black-and-white strip follows a number of characters from Nintendo’s Super Smash Bros. Brawl as they clamor over each other in an attempt to be the most supportive friend to the recently hospitalized Ganondorf.

“The comic had one panel of Toon Link looking excited, and people would trace that drawing over and over as different characters with the same pose and expression,” Lee says. After a stripped-down, isolated version of the drawing landed on 4chan, users on the forum named the template “fsjal,”where it began its wildfire spread across the internet. “I still see people online who have a trace of my drawing as their avatar everywhere,” Lee says.

The most popular Brian Lee creation, however, would come years later, a direct result of a self-imposed tradition Lee set up for himself near the end of his DigiPen studies in 2010.

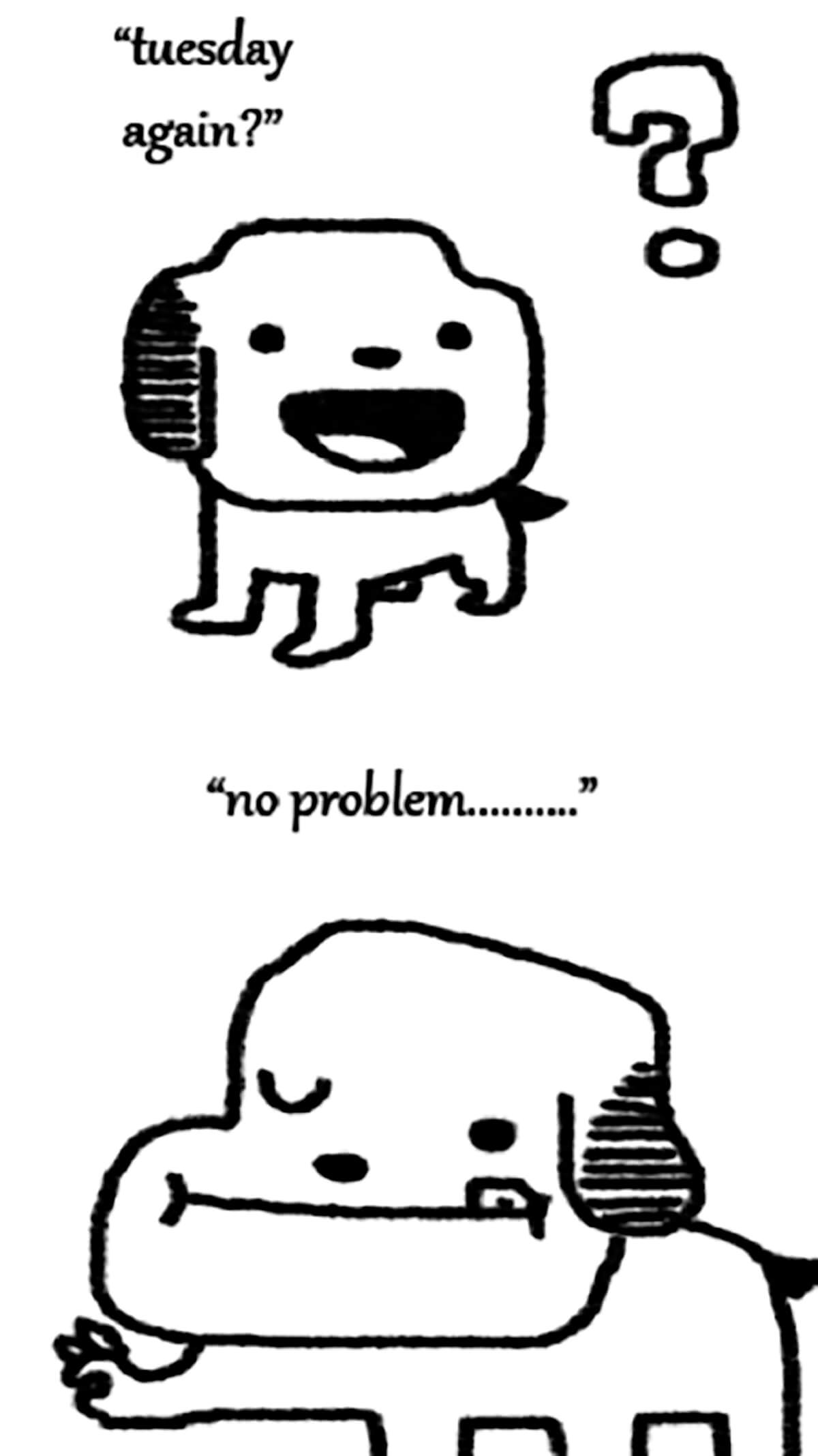

“I was doing ‘Draw a Dog Tuesday,’ where — whenever I could — I’d draw a dog on Tuesday and post it online somewhere, just to keep myself drawing,” Lee says. One fateful night in the fall of 2014, Lee realized 15 minutes to midnight that Tuesday was almost over, and he’d yet to draw a dog. “I was like, ‘I gotta go to bed, but I gotta draw my dog!’ So I just kind of scribbled out a really weird looking dog and put some text on it and posted it,” Lee says. “And … it kind of snowballed.”

The drawing is in many ways an inverse Garfield — instead of a cat that hates Mondays, Lee drew a dog that is unbothered by Tuesdays. “Tuesday again?” the happy dog asks, followed by, “no problem.” The image became an enormous internet sensation, generating just under 900,000 notes on Tumblr. The comic also spawned countless fan-made iterations in a slew of different styles, both drawn and animated, and even its own dedicated fan-run Twitter account with the sole purpose of reposting the image every Tuesday. It continues to be retweeted thousands of time each week. Some fans have written rapturous odes to the “Tuesday Again? No Problem” dog, describing it as a kind of affirmative saint of Tuesdays.

Take this description by Tumblr user extroition: “The fact that this happy fictitious dog exists now as a part of Tuesday, it lifts the spirit of me and many other people, and in many cases especially, has made Tuesday a kind of weekly holiday, which gives life a certain excitement and zest. I mean, just imagine how happy you’d be if something magical happened every Tuesday? Now it does.”

Four years later, Lee is still somewhat bewildered by his dog’s success.

“I’m pretty happy that if something I made blew up like this has, it was a really positive thing,” Lee laughs. “At first it’s exciting and funny, and then it becomes tiresome, and then it circles around to being, ‘That’s just part of the world now. It’s out there.’ For instance, I was at the coffee shop the other day and they had glass tables where people would slip business cards and drawings under, and someone had drawn a ‘Tuesday Again? No Problem’ dog and slipped it in there.”

Even with his full-time job programming games at King, Lee still finds the time to make art, work that continues to be warmly received in unlikely places. Most recently, an art gallery in Tokyo featured his work in its “Famicase” exhibition, a yearly event featuring fan-designed art for imaginary Nintendo games that the gallery prints and displays on real Japanese game cartridges.

“It was a pretty cool thing to participate in,” Lee says, “Again, I got into games because I loved both sides of it, the technical side and the art, so it feels cool to still be doing both those things.”