Video games have always been a transportive medium, evoking fantastical places and new horizons, but in the case of DigiPen MS in Computer Science graduate Esteban Maldonado, games have literally sent him around the world and back.

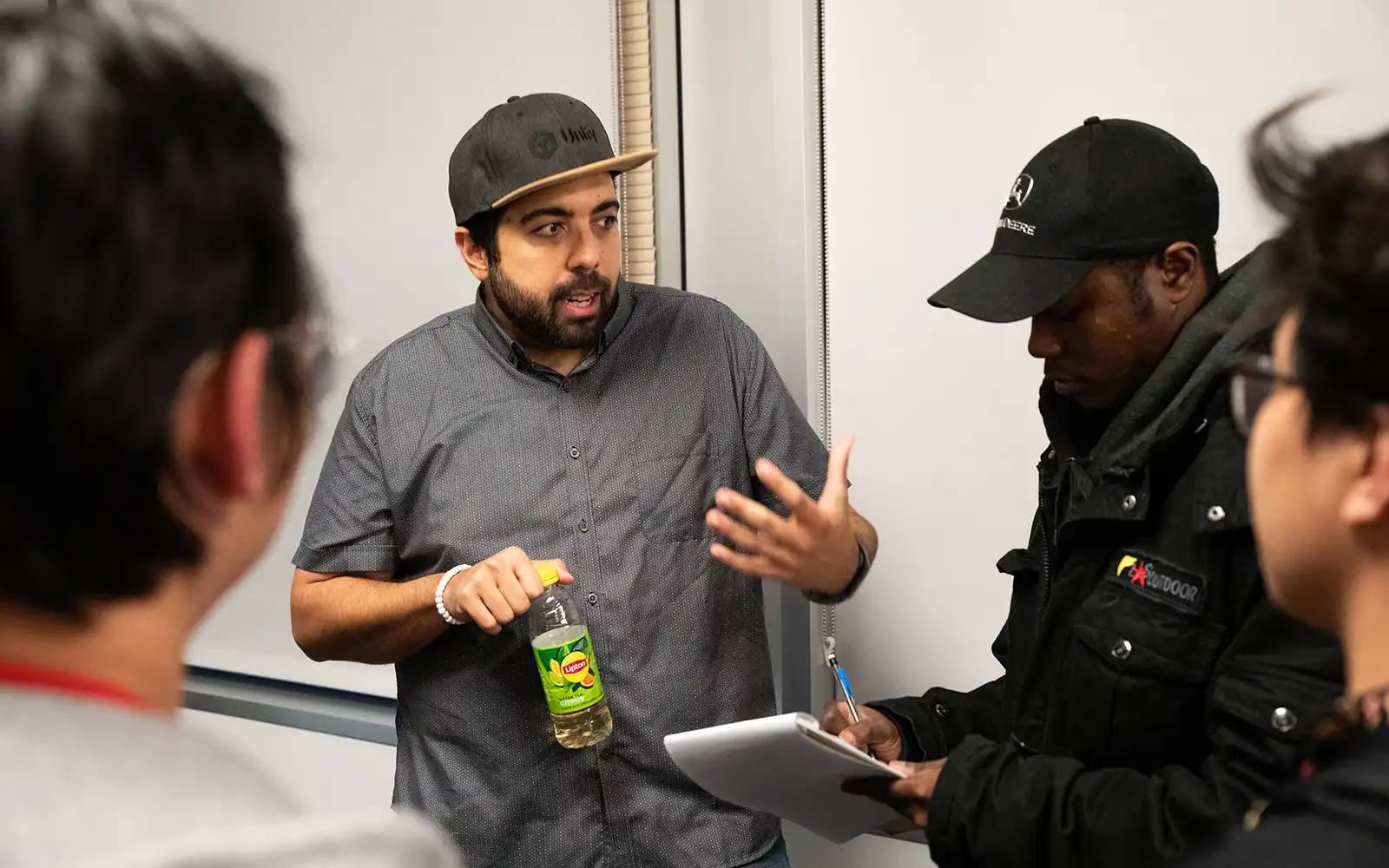

As a senior developer advocate with Unity Technologies, makers of the Unity game engine, Maldonado’s job is to connect with game creators at meetups, conferences, and events — sharing insights into the many features and benefits of the engine while listening to the needs and challenges of developer communities everywhere.

“I’m not going to lie, it’s been a lot of fun meeting developers from many parts of the world,” Maldonado says, citing past trips to countries in Latin America, Europe, and beyond.

His globe-spanning adventures can all be traced back to his undergraduate studies in his home territory of Puerto Rico. That’s where he first started taking courses on architecture and design.

“I thought that I wanted to be an architect, but that did not go well. I got bored really fast when I had to learn about the materials of walls and concrete, and my art skills weren’t super high quality,” he says.

Instead, Maldonado became interested in the coursework of his friends who were majoring in computer and electrical engineering — many of whom he regularly hung out with to play games. Eventually, after switching to a computer engineering major himself, a friend and fellow classmate petitioned for an elective in game development using Microsoft’s XNA framework.

“I found game development to be the perfect mix of the objective puzzle-solving aspect of programming, with the visual and creative side of what I loved in architecture. I was a gamer all my life, but it never occurred to me that I could actually make games myself,” Maldonado says. “I helped my friend to get signatures, and we encouraged enough students from computer science and computer engineering to start our own game development class.”

Several students from that inaugural class would go on to form an indie game studio that Maldonado also joined, helping ship a side-scrolling mobile platformer about a rogue pig in a bacon factory. Their game would, in turn, earn Maldonado and his teammates an international trip by becoming a regional winner and international finalist in the 2013 Microsoft Imagine Cup, an annual student competition held that year in St. Petersburg, Russia.

“We didn’t win the thing in Russia, but we didn’t care,” Maldonado says. “We had a lot of fun.”

By the time he graduated with his bachelor’s degree, as Maldonado and his studio teammates began to consider their next moves and whether a future in games was still possible, a friend of Maldonado’s planted the idea of enrolling at DigiPen — an idea that was intended as a joke.

“I still remember to this day when my friend said, jokingly, ‘What are you going to do, go to DigiPen?’” Maldonado recalls with a laugh. “That actually happened. And that’s how I found out about DigiPen’s existence.”

Instead of laughing it off, Maldonado took the idea seriously, and he soon found himself traveling more than 3,700 miles from home to continue his studies in Redmond. Despite coming to DigiPen with a prior degree, Maldonado started out by taking undergraduate courses in order to bolster his game programming chops — partially supporting himself as an instructor for DigiPen’s K-12 summer programs — before transferring to the MS in Computer Science program.

A lot of the success factor really is outside of the classwork that you do.

While Maldonado can easily point to a wealth of knowledge he gleaned in the classroom — including critical topics like graphics rendering, data and memory management, and general C/C++ programming — he says he found just as much value from his extracurricular activities. For him, that included going to the Game Developers Conference in San Francisco, attending as many on-campus Company Day events as possible, and checking in frequently with the Office of Career and Alumni Relations for help with updating his resume and portfolio.

“I also went to mini-networking events — as many as I could,” Maldonado says. “A lot of the success factor really is outside of the classwork that you do.”

His persistence paid off near the end of his studies when he landed two successive software engineering contract positions at Microsoft and Amazon Game Studios. All the while, Maldonado was making a strong effort to complete his master’s degree at DigiPen, an achievement he finally unlocked in the spring of 2019. That’s also when Maldonado got his foot in the door at Unity with a four-month internship, and by November, after a short stint at Turn 10 Studios, he managed to get hired back on at Unity as a full-time software engineer.

For the first two years, Maldonado worked primarily on tools and plugins for the Unity engine, particularly in the area of software version control features. Eventually, he says, he began to miss the joy and camaraderie of actual game development work.

“I started to wonder what was out there, and I applied to a few roles,” Maldonado says.

A fellow Unity coworker who had previously worked on the advocacy team herself suggested Maldonado might be a good fit for an opening there — pointing to his past teaching gigs and some community engagement work he was already doing.

“She and I had met and hung out at game development events in Puerto Rico,” Maldonado says. “Before deciding to join Unity or even leave the island, I had already interfaced with that team. So, it was kind of full circle.”

Using some of the materials he was already working on for teaching developers how to understand version control systems, Maldonado applied and was hired on to the advocacy team. Today, Maldonado’s job is a mix of hands-on development and game community outreach. Instead of working on new features for Unity directly, however, Maldonado’s development work now sees him building cool things within the engine in order to showcase its capabilities to other would-be adopters.

“We use our game development skills to deliver technical sessions on various topics. The one that I have been representing the most has been multiplayer solutions and how to make online games using Unity technology,” he says.

For one recent livestream, Maldonado presented on how to bring multiplayer functionality to a simple 2D scene in Unity — showing off the various features one could incorporate within a 10-minute, one-hour, and full-workday time window.

“That took at least a day and a half of prep work, because I literally had to time myself and be like, ‘Ten minutes, here we go. One hour, here we go,’” he says. “And then I dedicated a workday to just to see how far I could get.”

Beyond the prep work and public speaking, Maldonado says a big part of his job involves meeting with developers wherever they’re at in their development journey.

“It’s a technical role, but at the same time it’s a very human-focused role,” Maldonado says. “It requires a good base level of empathy.”

Over the course of his four years on the advocacy team, Maldonado has indeed established a plethora of human connections, both through online events and in-person travel opportunities. From Seattle-area meetups and game jams to international conferences and beyond, Maldonado has enjoyed interacting with game makers the world over and witnessing firsthand how tools like Unity are helping developer communities grow and flourish.

When asked about some of his favorite destinations, Maldonado gives a special shout out to thriving indie scenes in places such as Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Colombia, and of course, Puerto Rico. Speaking of Puerto Rico, Maldonado says he was thrilled when he recently got to attend an in-person game jam back in his home territory, where he watched a team of young developers create their first game in Unity, complete with online multiplayer.

“Their first Unity game was a multiplayer one. I was like, ‘That’s freaking cool!’” Maldonado says. “In 48 hours you can actually come out with a prototype or something fun that you can even take online.”

And it’s not just game developers who are discovering the benefits of “game engine” technology like Unity, Maldonado says.

“Unity has been used for UI for regular mobile development apps. It has been used for rendering geometry in electric vehicles,” he says. “It’s also used for simulations and different kinds of training, including medical training.”

It’s even gained traction in architecture, he says, the field Maldonado pursued in his early undergraduate days.

“I recently met one of the directors of a Seattle architecture firm that did the Amazon Spheres. They use Unity and VR to showcase models of the design before they even hit the ground, so that way people can actually get a preview of the space before it’s been built,” Maldonado says. “So, yes, I highly encourage people to really look for jobs outside of games as well, because there are a lot of cool problems [to be solved] out there.”