Though Mark Henne is now at the helm of DigiPen’s Master of Fine Arts in Digital Arts program, his background isn’t actually in fine arts. He’s a computer scientist, but one who also has never held a job as a traditional programmer. How then, does one describe his background?

Computer animation pioneer, perhaps. As a technical director at Rhythm and Hues, and later at Pixar, Henne was one of the first people in the animation industry to tackle the problem of art-directed organic movement. He worked on classic commercials like the Lexus “Car Cloth” commercial, helping make the car’s second skin smoothly peel off to reveal the newer model beneath. That commercial was featured in the New York Museum of Modern Art’s presentation “The Art and Technique of the American Commercial.” At Pixar, he came on board during the production of Toy Story and stayed for another 18 years, working on a few more Oscar-winning animated films along the way.

I come from a family of teachers. My father was a teacher, my grandfather was a teacher, and my brother is a teacher.”

Henne first became interested in computer science before computer animation was really a field, but he was uniquely well-positioned to get in on the ground floor thanks to that. In the late ’70s, his father was working at the University of Illinois, which just happened to have a graduate computer science program that was focused on teaching teenagers how to code.

“In the time when I grew up, having experience with computers was kind of rare,” he says. “That was my in, gaining access to the labs there. I started programming well before anybody else surrounding me.” He also had a lifelong interest in art and design, making his eventual job a natural fit. At the time, the original Star Wars was just coming out, and the world of visual effects was entering a renaissance, he says. Even by the early ’90s, however, most visual effects still weren’t made with computers.

Henne had originally planned to major in architecture, but after realizing that he could put his math and science skills to use in the emerging field of computer graphics, he changed direction and pursued computer science instead. From the very beginning, he says, he was interested in the problem of creating natural-looking movements on screen.

“It’s not just the texture, it was that the skin itself didn’t deform in a natural way,” he said, complaining about the mechanical nature of early computer-animated figures. “There would be seams at all of the joints, so the designs were very robotic. I was interested in modeling more organic forms, and how to represent internal anatomy and its effect on the skin’s surface. The muscle, the bones, and how that influenced external shape.”

He went on to pursue an MS in Computer Science from the University of California in Santa Cruz, drawn there after meeting Dr. Jane Wilhelms, a computer scientist with undergraduate and graduate degrees in zoology and biology, respectively. She shared a similar passion for bringing organic forms to life on the screen and had actually worked as a consultant for Lucasfilm, making the Star Wars movies that had originally helped inspire Henne’s passion for computer animation.

There’s a huge diversity of ideas within the MFA.”

After getting his master’s degree, Henne dived into digital animation at Rhythm and Hues. There, he says, he began developing new tools to make his artistic vision come true.

“At the time there was no software that could create the kinds of things that I wanted to create,” he says. “So I made the software myself.” Though he was doing the type of work he wanted to be doing, he eventually decided he didn’t want to be in Los Angeles. He checked in with some contacts at Pixar, where he’d done an internship during school, to see if they had anything for him in the Bay Area.

“The people at Pixar were working on a new movie about toys that sounded really exciting,” he says. “They had another 10 or eleven months left to go on that, and so they showed me around and said, ‘You should come and help us finish this film.’ So I did!”

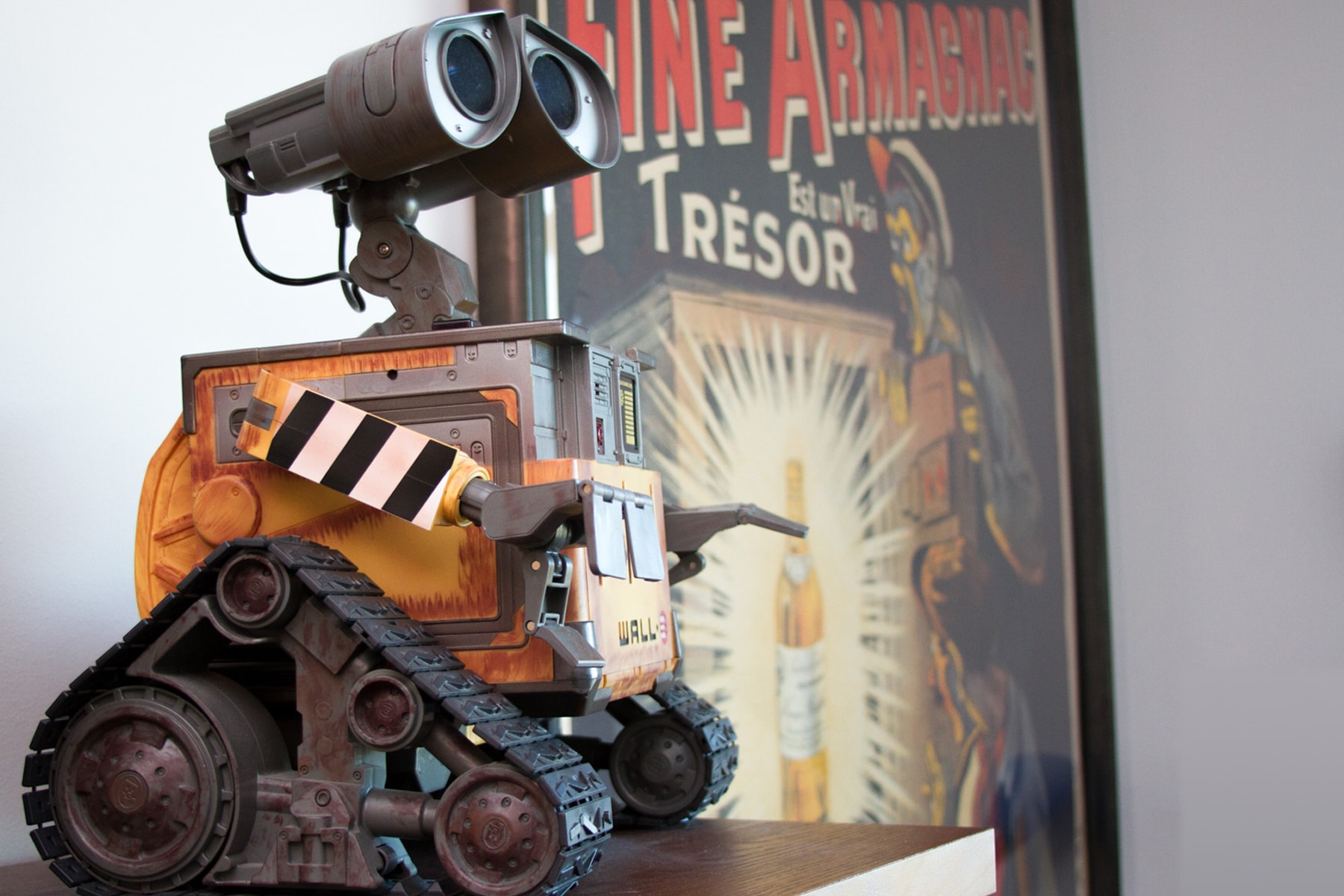

That film, of course, was Toy Story, which won a special achievement Oscar for being the very first feature-length computer-animated film. After that, he worked as hair and clothing supervisor on The Incredibles, as a crowd and simulation supervisor on Wall-E, and in hair and clothing simulation again on Brave, among other roles.

However, after 20 years in production, he felt it was time for something new. He joined DigiPen in 2012 as a professor in the Bachelor of Fine Arts in Digital Arts and Animation program.

“I come from a family of teachers,” he says. “My father was a teacher, my grandfather was a teacher, and my brother is a teacher. So I was kind of drawn to it.” He jokes that, additionally, his wife told him the only place that would get her out of the Bay Area was Seattle. His slow journey up the West Coast complete, he settled in to teaching, overseeing the BFA program’s senior projects and teaching the single computer science course required in the major.

“I’ve enjoyed the change and having an opportunity to give back and help the next group develop their skills and create something new,” he says. After three years in the BFA program, he stepped in last spring to direct the MFA program. Since then, he’s helped introduce some subtle changes to the program curriculum and application process.

We’re strengthening the calling card that they have with their thesis.”

The program, he says, had initially been focused on character design, requiring students to submit a portfolio demonstrating proficiency in figure drawing and gearing coursework towards character creation. However, that wasn’t always aligning with the wider array of interests of the students, he says.

“There’s a huge diversity of ideas within the MFA,” he says. “Roughly half the students were interested in character design and the other half interested in something else — a wide variety of things. Some are kind of a mix of character design and something else. Some are interested in narrative — say creating books, whether those are printed books or interactive storybooks.” Naturally, there’s a similar diversity of ideas in MFA applicants, and Henne adds that the character design focus forced them to occasionally turn away otherwise qualified applicants in the past.

“There have been [applicants] that, as designers, we would have liked to have in the program,” he says, “but we couldn’t accept them knowing that they would have to jump in the deep end of figure work as soon as they entered the door.”

To open the program up, Henne says, they’ve changed the acceptance requirements, creating three separate areas of focus that students can apply to — character art, concept art, and environment art — with requirements tailored to each. Once accepted, students all study the same course curriculum, but it’s been massaged to allow students more freedom to pursue their particular area of interest.

Within the program itself, the number of credits dedicated to thesis work has been doubled, which is in line with most other major digital arts MFA programs nationwide, Henne says. They’ve also dropped character design as a first-year requirement, instead offering it as an elective, and have beefed up the first year to focus more on teaching fundamental digital art skills. This gives students an opportunity to learn more about the possibilities available to them in digital arts and to figure out what most excites them.

The overall goal, he says, is to encourage a more diverse array of thesis projects, as well as to give students the space and tools to pursue even more ambitious projects.

They can really sell their individual talents with a substantial portfolio piece.”

“We’re strengthening the calling card that they have with their thesis,” Henne says. “They have more to show and talk about by focusing more on that thesis.” Strong, unique thesis projects have certainly helped previous MFA grads to land jobs. Isabel Anderson, who designed and 3D printed a line of empowered female action figures for her thesis, landed her dream job doing very similar work at Funko shortly after graduation. Tara Jaiyeola had a passion for parade puppets, and for her thesis she built a 15-foot-tall puppet, performed in it for motion capture, and then created a digital toolkit for making prototypes. That project helped to secure her a spot at Disney Imagineering.

Judging from those and other success stories, Henne says that encouraging even more adventurous, ambitious thesis projects can only be a good thing. A more diverse array of portfolios, he notes, means “more niches to fill.” Beyond that, giving students more time to focus on their portfolio helps them where it really counts — the job search.

“They can really sell their individual talents with a substantial portfolio piece,” he says. “And not just by presenting themselves as an artist, but as a thinking artist.”