At most colleges, there’s a very slim chance your professor will hand you a Switch controller and ask you to play The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild in front of the class. But during MUS 150, one of the first semester classes for the Bachelor of Arts in Music and Sound Design degree program at DigiPen, students are asked to do exactly that.

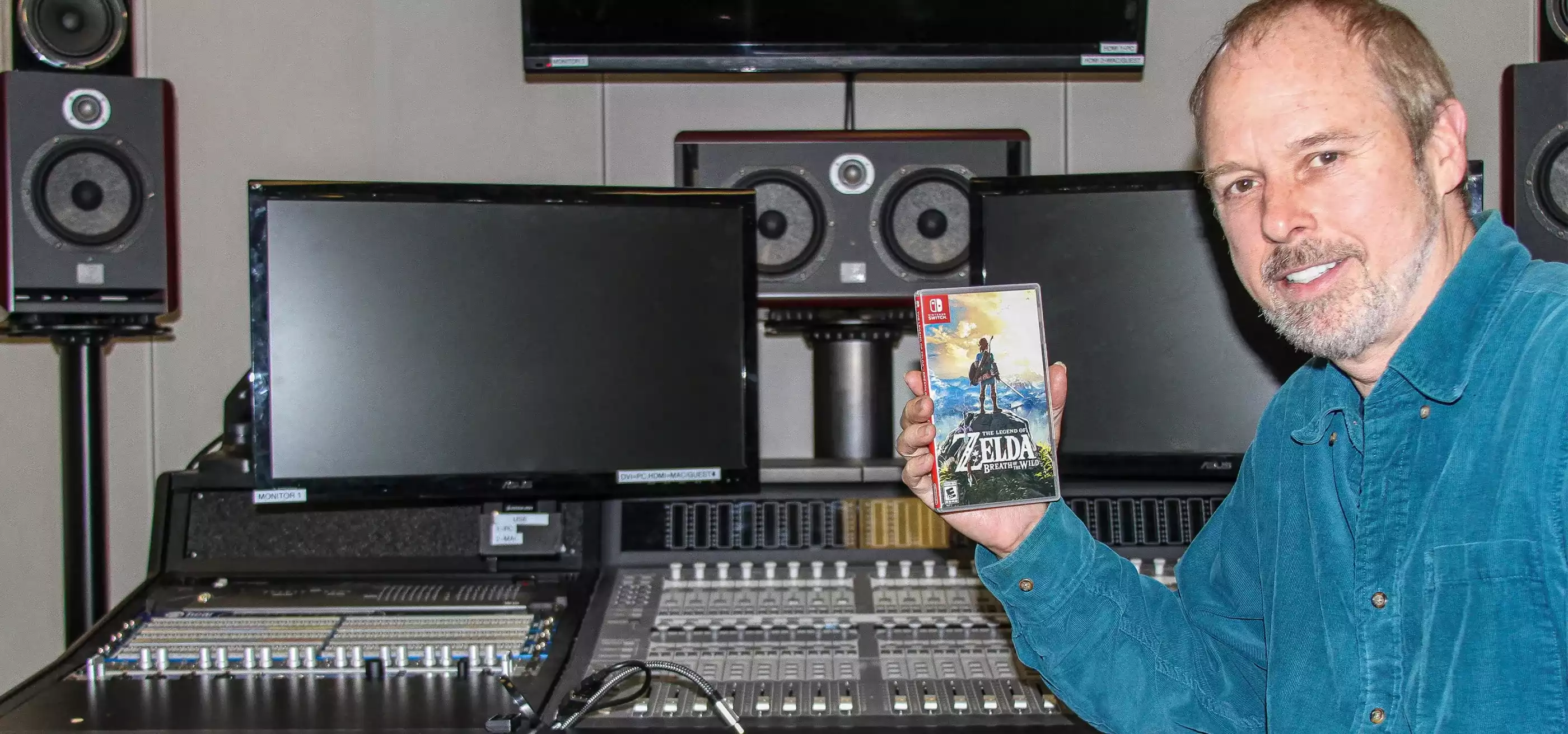

“I use Breath of the Wild as the apex example of non-linear game audio,” says program director and former Nintendo Software Technology audio director Lawrence Schwedler. The contemporary video game classic has served as the basis for many of Schwedler’s class lectures and assignments since its release in 2017, acting as a springboard for introducing some of the program’s overarching core concepts.

One of those core concepts is the aforementioned idea of “non-linear” audio. “I use Breath of the Wild because its approach to this is very sophisticated. But as a larger concept, non-linear audio is a little tricky to wrap your head around, particularly for music,” Schwedler explains. In a film or television score, a composer or sound designer knows exactly when an intense car chase, a fated kiss, or a dramatic death is going to happen. As such, they can write in crescendoing strings or bombastic drums accordingly. “But every time a gamer sits down with a controller and boots up a game, it’s an almost unlimited set of potentials that could play out in this infinitely branching structure,” Schwedler explains. “For all you know, the player could literally just walk in circles in the forest forever. Regardless, the goal is to have the game sound as if the composer knew exactly what was going to happen in your particular play through.”

In class, Schwedler and his students spend time playing through the opening sections of Breath of the Wild, analyzing the game’s expertly executed approach to this concept. “Even though Breath of the Wild’s overworld music is very sparse and minimalist, the music in the game is almost always used purposefully, never just as a soundtrack,” Schwedler says. “If you listen, even just an encounter with a simple, weak bokoblin on the plateau, it sounds as if the composer knew exactly what would happen in that particular battle.”

Students explore how the game’s combat music was written in dynamic, seamless fragments that ramp up in intensity depending on the player’s proximity to enemies, whether or not the enemy has spotted Link, whether or not combat has officially been initiated, and whether or not a blow has just landed. “Then, if you die, you need the music to transition seamlessly into the game-over sequence, or if you win, you need it to transition seamlessly into a victory stinger,” Schwedler says.

But before Link even gets outside and meets the game’s first enemies, Schwedler and his class spend quite a bit of time just on the game’s opening cutscene and tutorial phase, analyzing details as minute as the sound effects in the menu screen. “We go very slowly. We spend 20 minutes in the Shrine of Resurrection just walking around and listening to Link’s footsteps!” Schwedler laughs. “We listen to how they sound wet versus dry, whether he’s barefoot or has the boots from the Hylian Trousers on, and whether or not he’s walking or running on sand or stone. These are subtle differences, but they do so much for the immersion.”

After spending time analyzing these elements, students have to jump in and recreate a number of them on their own from scratch. In one assignment, students recreate the soundtrack and voiceover from Breath of the Wild’s opening cinematic. “You hear a sort of electronic tone, then a voice going, ‘Link. Wake up, Link! Open your eyes!’ But that voiceover starts sounding very muffled and far away, which students also have to recreate in their mixer, running automation on what’s called a low-pass filter,” Schwedler says. In another tricky assignment, students are tasked with transposing and recreating the two otherworldly sound effects that occur when Link first receives the Sheikah Slate, as well as the reward stinger that follows.

Students have to transcribe and recreate these two tricky Sheikah Slate sounds in an early Breath of the Wild-based assignment.

“First they have to transcribe, literally write down what they hear as far as pitch, rhythmic intervals, and harmonic dictation, which is hard, because these two sounds are very unusual,” Schwedler says. Then, students have to take what they’ve written into the digital audio workstation Logic Pro and recreate the sounds to the best of their abilities from scratch using the software’s synthesizers and effects. “In one first semester assignment, students are getting multiple lessons in what this amazing Zelda sound team does,” Schwedler says. “There’s so much going on in those 15 seconds of the game, but you’re just swept away in the immersion of the moment.”

Students seem to be swept away by the assignments as well. “They just love it,” Schwedler says. “They very much like that we’re using a relevant example that they’ve almost all played. I think it’s something really important that we offer here at DigiPen, that our instructors are teaching these ideas not as an academic science we learned 30 years ago, but as people who are actually engaged and invested in what’s happening right now.”