When Associate Professor Vanessa Hemovich first started teaching a new Psychology 101 course at DigiPen in 2011, game students weren’t exactly psyched about it. Although she had taught psychology courses for over a decade at four other colleges, DigiPen was different. “Students didn’t come to DigiPen to learn about psychology,” Hemovich says. “Nobody was really all that interested or wanted to be there. In the beginning, I had to fight for relevance a little bit — for why we need to teach psychology at DigiPen at all.”

Hemovich, who earned a Ph.D. in Social Psychology at Claremont Graduate University, also happens to be a lifelong gamer, a self-professed fan of sci-fi military shooters and games like Ori and the Blind Forest and Riven in particular. To her, the connection between games and psychology is anything but tenuous, and the chance to prove it to skeptical students that first week of class felt less like a daunting challenge than a fun opportunity to combine two of her life’s passions.

“The question really isn’t ‘How does psychology apply to games?’ but ‘How does psychology not apply to games?’” Hemovich says. Eight years later, Hemovich has more than proved her point. In 2011, when she first started teaching at DigiPen, offerings in the subject were limited to only four PSY 101: Introduction to Psychology classes. Popularity for the course quickly grew, and, in response to student and industry demand, DigiPen now offers 16 introductory courses a year, along with more than a dozen upper-level courses in cognitive, social, and research psychology. On top of that, in a first for DigiPen, a brand new Psychology minor has recently been approved. Set to be introduced in the near future, the new academic pathway will also include a number of new psychology courses currently in development for students interested in expanding their application of psychology to foundational game design, art, and programming tracks.

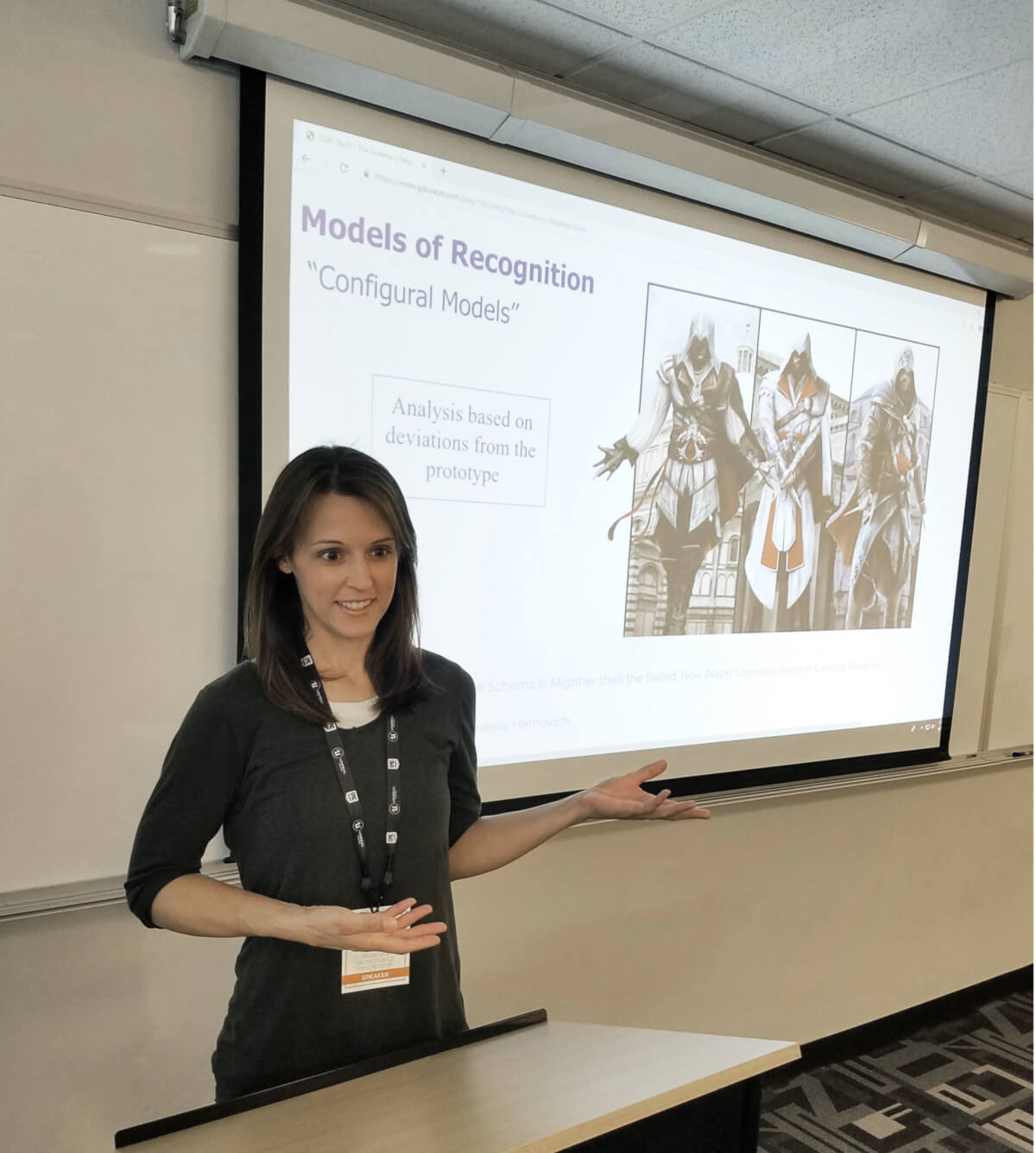

Hemovich’s effect is being felt outside DigiPen in the larger game industry as well — her Game Developer’s Conference UX Summit talk, “The Schema Is Mightier Than the Sword,” was ranked the most popular session of 2018. She was invited back this year for a follow-up presentation, which ranked as the second most popular session of the 2019 UX Summit. “To be able to show students and industry professionals the science of how people think and behave and tie it to games, for me, it’s fascinating,” Hemovich says.

So then, what does psychology have to do with video games, and why are DigiPen students increasingly eager to dive into the field? “There’s a saying around here: ‘Psychology is to game design as math is to computer science,’” Hemovich says.

At its most fundamental level, the three main goals in psychological science are to predict, understand, and control behaviors and attitudes. For a game designer hoping to create an experience that’s intuitive, fun, accessible to a wide audience, and consistently engaging, being able to describe, explain, predict, and control content to impact what a player might do and feel in any given situation is invaluable. To see why, it’s helpful to understand what happens when games are developed without any psychological grounding.

“Not understanding how basic psychological principles of attention, perception, information processing, or flow impacts game design tends to manifest as expensive problems later on to try and resolve during the testing phase,” Hemovich explains. “This might include anything from loss of player focus to missing HUD notifications, or just general frustration with a game mechanic. These kinds of player issues might easily have been prevented or even outright avoided earlier in the process through a firm understanding of psychology and UX. Incorporating psychological applications in UX from the start helps inform better UI and design choices that ultimately creates more favorable user outcomes and positive player experiences. Psychology gives us a useful lens to help create more immersive and enjoyable content for players, and the wealth of established psychological science behind usability and testing creates more data-driven design choices for game studios and dev teams to draw upon and utilize.”

As Hemovich explains it, the industry’s most successful, widely-loved video games incorporate a lot of these psychological models so subtly, you probably don’t even notice them. Part of the joy of Hemovich’s classes are when students learn these models for the first time and begin to reverse engineer their own favorite games in class, often sparking spirited group discussions in the process.

“For example, most students catch onto classical conditioning very quickly, like Pavlov’s bell, and they go, ‘Oh, OK. I get this.’ But then when we tie it to games, the room just explodes with students offering examples of ‘Is this what happened in this game?’ and ‘Is this why I played that game so long?’” Hemovich says. “Take Fortnite, for example. Treasure chests make a certain noise when you get close to them and it gets louder as you get closer — this sound means there’s something good in the game. Then an a-ha moment will happen, and a student will go, ‘Oh yeah! That happened to me with the color yellow in The Last of Us,’ a very hidden directional cue a lot of gamers consciously missed but followed.”

Those eight years of class discussion have directly informed Hemovich’s curriculum, which is constantly being shaped by the psychological connections her students are making to new games. “They’re applying psychology to games in ways I haven’t thought of yet, and I absolutely carry that forward into the next class,” she says.

While only Bachelor of Arts in Game Design students are required to take psychology courses as part of their core curriculum, now that the word has gotten out, Hemovich is seeing more and more students from computer science, sound design, and other programs taking Psychology 101 and upper level psychology courses as electives. “They really get interested when we start talking about system processing, AI, menu designs, or how people are biased in attending to the thing they think is most important to attend to. I think it’s because there’s a fundamental [desire] to understand how their players are thinking,” Hemovich says.

Students who do ascertain how their players think are finding it’s having an outsize effect once they graduate and enter the industry. “We often have students going into the field, to both indie and triple-A studios, and suddenly they find they’re the sole person in the room who understands many of these concepts. They’ll raise their hands in a meeting and say, ‘That sounds like we’re putting too much cognitive load on the player.’ Sometimes they’ll get a bunch of blank stares, but then suddenly they’re the most popular person in the room,” Hemovich says. “On more than one occasion I’ve had graduates report back and say, ‘I’m so glad I took psychology classes. I was able to correct someone or put in my two cents on something else, and I felt very informed.’”

Hemovich was recently promoted to the Assistant Dean of Faculty Development, a role that allows her to design and implement professional development and support opportunities for DigiPen faculty. Among these includes publishing The Slate magazine, which highlights annual research, awards, and notable achievements of institutional faculty. The new position, in theory, means she should be teaching less. “I’m supposed to teach maybe one or two classes a year, but I’m currently teaching about five,” Hemovich says. “I can’t quite help myself, because the students here are just incredible.”

On top of that, she’s recently published two book chapters (one on gender in superhero narratives and another on the Call of Duty series’ evolving depiction of militarism) and spoken at conferences in Sweden, Canada, and the Bahamas. She also organized a DigiPen Colloquium Speaker Series featuring industry guests like former Fortnite UX director Dr. Celia Hodent, brought an official Unreal Engine Masterclass to campus, and helped set up an Epic Games internship program that led to full-time jobs for three graduates working on Fortnite fresh out of school. Today, she’s undertaking two new research studies, one on the effect of win/loss outcomes on pro-social behaviors in violent first-person shooters and another on gender representations in board games with fellow DigiPen lecturer Jeremy Holcomb. She’s also gearing up for her third annual presentation at the PAX Dev conference in Seattle.

“I think there’s a lot of education that’s happening everywhere, and it’s just this perfect storm changing how psychology is viewed in the game industry,” Hemovich says. “It’s just become more central to a lot of the conversations that are happening.” In the end though, even a seasoned pro like Hemovich admits there are some games that defy psychological explanation. “In class, we have a really nice discussion around Dark Souls and how they didn’t follow operant conditioning’s rules of reward and reinforcement, and how they got away with it,” she says. Keeping up with trends in video games and discovering new industry twists on established mechanics means that Hemovich is constantly revising her courses to maintain relevance and stay informed. There is no perfect recipe on how to make games, but learning how to apply principles of psychology is proving to be a critically important tool for any developer’s toolbox.