Back in the early ’90s, Disney wasn’t just dominating movie screens. The animation giant had also found success in a whole new world of video games.

The 1993 Sega Genesis platformer Disney’s Aladdin was the console’s third best-selling title ever, bested only by the first two Sonic the Hedgehog games. Disney’s follow-up, the 1994 Sega Genesis and Super Nintendo platformer The Lion King, found similar success, selling 4.5 million copies worldwide. Recently remastered for modern gamers on PlayStation 4, Nintendo Switch, Xbox One, and PC as Disney Classic Games: Aladdin and The Lion King, the re-released titles are also a chance to experience a bit of DigiPen history. For a number of DigiPen’s animation faculty who worked for Disney at the time, the two games were some of their earliest official assignments.

In between films, while Disney figured out what its next feature would be, the company often assigned animators to smaller side projects with the “Animation Services” department. That could mean anything from a Fanta soda commercial starring Mickey Mouse to video game tie-ins.

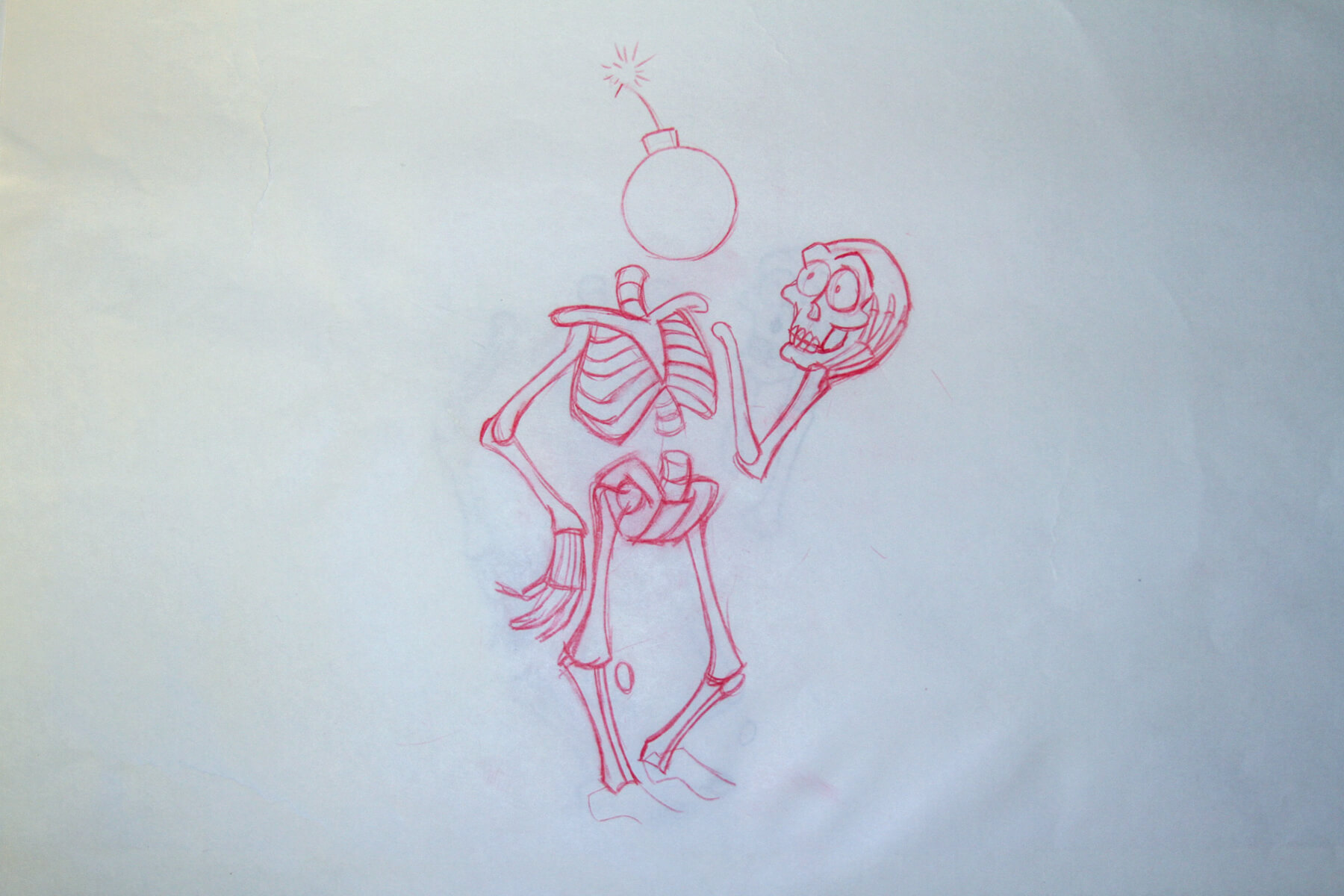

“Gaming was nowhere near what it is now,” Jazno Francoeur, DigiPen’s program director for the Bachelor of Fine Arts in Digital Art and Animation, says. “The constraints of consoles and games back then was ridiculous. By dint of that, we had some very strict limitations to what kinds of animation cycles we could do. Sometimes I’d only have four drawings to do a cycle.” Francoeur, who worked on the Aladdin game’s animated traps, obstacles, props, and visual effects, says those limitations could alternately be infuriating and invigorating.

“I remember being frustrated only being able to do the bare essence,” Francoeur says. “You had feature film animators working on this wanting to get the most expression possible out of these very limited cycles. At the same time, it was great, because you got instantaneous results — unusual at Disney. On a film, it was very difficult to get something approved by the director. The pipeline was very complex. On the game, you’d show the director stuff, and they’d go, ‘Approved. Next! Approved. Next!’ It was nice to be able to whip stuff out like that.”

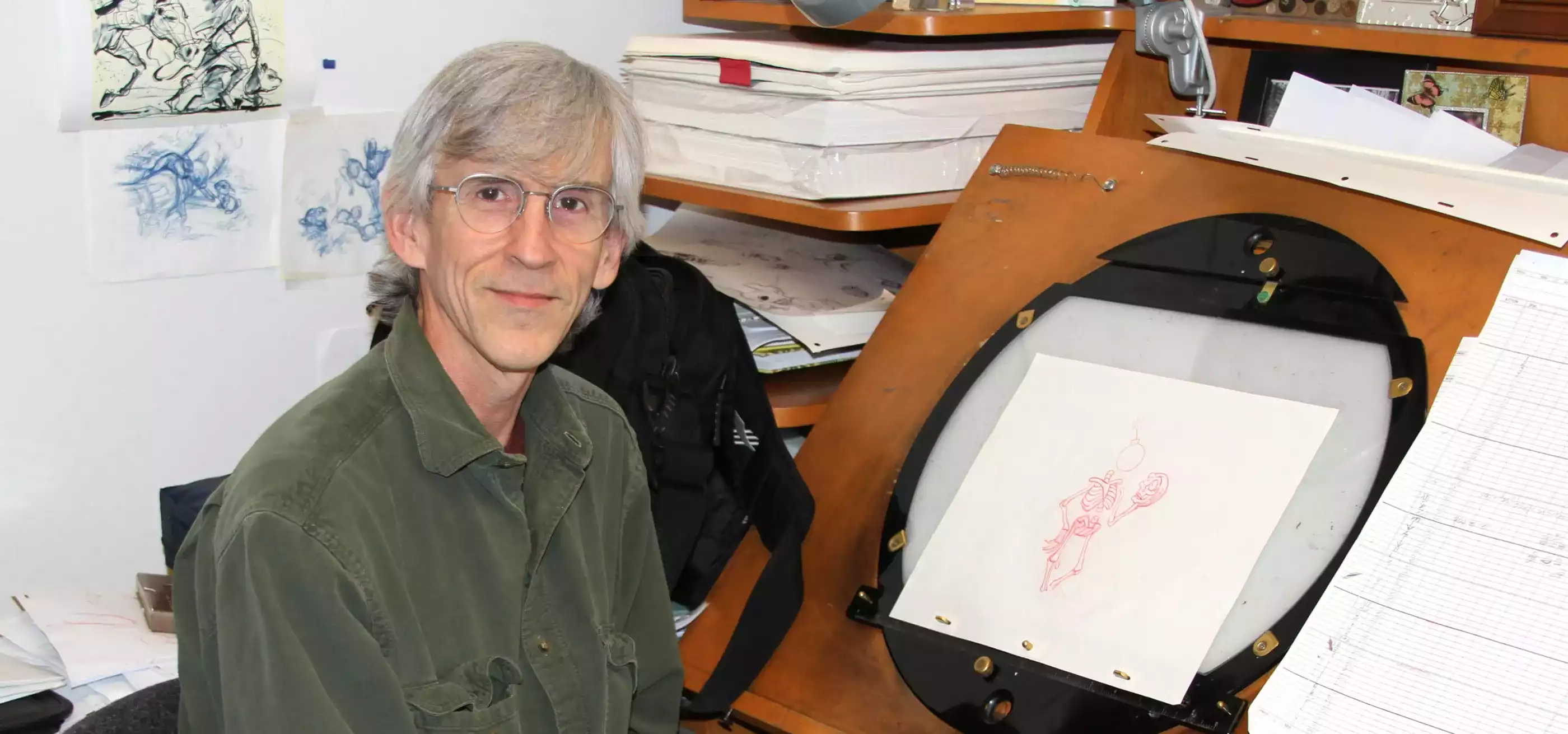

Dan Daly, faculty chair of the Department of Animation and Production, was hired full-time at Disney just as production was wrapping up on the Aladdin film. “All I got to do was put some of the tassels on the flying carpet in one scene,” Daly laughs. “But the game was fun because I worked on characters I didn’t get to touch in the movie.” Daly fondly remembers working on animation cycles for the game’s final boss fight with Jafar. “They’d give me a full-figure Jafar doing an attack with his staff. Sometimes you’d only have a quarter of a second, so you had to make it work, using a lot of drags and wipes to accommodate for that. We still put everything we knew about the 12 principles of animation into it, even if it was simplified.” For some, those restrictions were the best part of getting assigned to a game.

“It was actually a really fun learning process seeing how much you could stylize the action to meet the limitations, while still achieving clarity,” senior animation lecturer Richard Morgan says of the Lion King game, his first project as a full-time Disney employee. Morgan, who worked on The Lion King film as an intern, was assigned to work on Mufasa and Simba in the game adaptation, animating their run and jump cycles. “You’d have to figure out how to do one main, simple action that could reset into the character’s neutral pose. It was never like, ‘We need Mufasa to deliver a dramatic monologue.’ More like, ‘He moves forward, growls, tries to grab you, then returns to the rest pose.’ Simple stuff, but really fun for that reason!”

Despite the animation limitations, both games were hailed for their excellent visuals by reviewers at the time. “The father of limited animation, Hal Ambro, once said that if the design is really good, people will forgive some of the animation,” Francoeur says. “It was definitely simplified, but the design in those games was still really on point — you had a who’s who of Disney feature animators working on them! That’s probably why people still remember those games so fondly.”