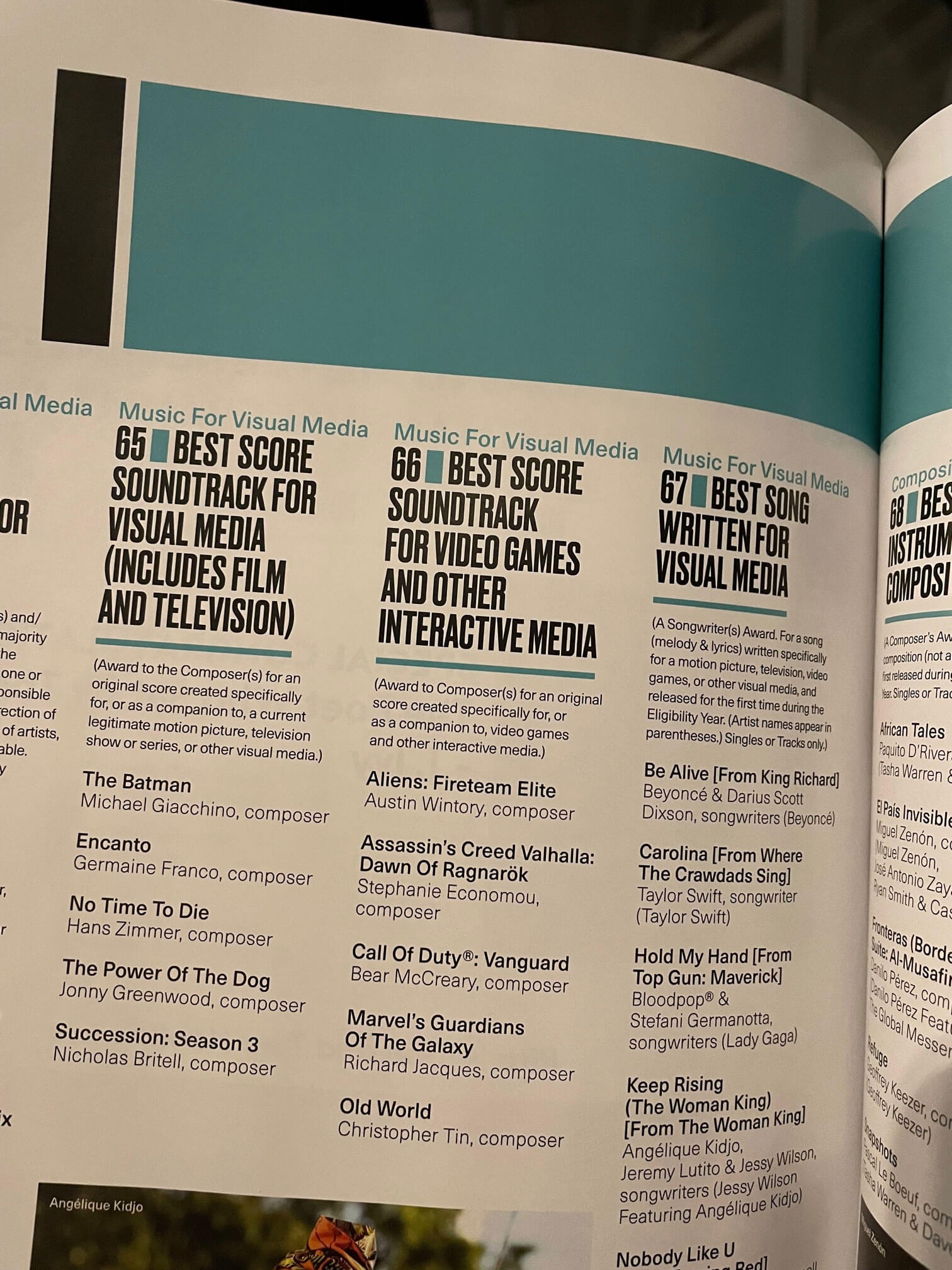

On February 5, composer Stephanie Economou made history by becoming the first person to win a GRAMMY for a video game soundtrack. The award was in recognition of her work on Ubisoft’s Assassin’s Creed Valhalla: Dawn of Ragnarök, which had been nominated alongside four other contenders in a new GRAMMY award category, Best Score Soundtrack for Video Games and Other Interactive Media. At the end of her acceptance speech, Economou called attention to the significance of the award by thanking those who helped make it a reality.

“Lastly, I just want to recognize all of the people who fought tirelessly to bring this category of video game music into existence,” she said. “Thank you for acknowledging and validating the power of game music.”

It was a moment DigiPen faculty member Brian Schmidt likely won’t forget anytime soon — not only for the fact that he got to witness it firsthand as a member of the audience. He was also one of the many unnamed individuals Economou was alluding to.

“Having the Recording Academy recognize video game scores as a unique enough form of art to recognize it with what is the highest award in music, by many people’s accounts, is pretty cool,” Schmidt says.

Schmidt himself is no stranger to video game music. After getting his start at Chicago-based pinball manufacturer Williams Electronic Games in 1987, he spent the next three decades as a professional game composer, sound designer, and computer engineer for sound chips and other game audio tech. In addition to teaching as a principal lecturer for DigiPen’s Department of Music, he also serves as president of the Game Audio Network Guild (also known as G.A.N.G.), a nonprofit organization that works to advance excellence in game audio through a combination of networking, advocacy, and more.

As a prominent and prolific figure in the field of game audio, it should come as no surprise to hear that Schmidt was also an early participant in the behind-the-scenes effort to bring video game music to the GRAMMYs. According to his account, it all began thanks to the efforts of a fellow composer who organized an eventful game music summit in late 1998.

“I got contacted by a game composer whose name is Chance Thomas. And he was gathering a group of game composers to meet with what at the time was called NARAS, the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences,” Schmidt says. “They are now called the Recording Academy, but NARAS was the organization that put on the GRAMMYs.”

Our goal was to basically say, ‘Hey, here’s what game music is now. You might be thinking Mario, Donkey Kong, stuff like that. It’s not like that anymore.’

The group’s mission was to convince the academy members that music made for video games should be eligible for recognition at the GRAMMY awards. Previous award categories, such as for best soundtrack, had been explicitly limited to scores written for film or television — with no path to consideration for interactive media.

“Our goal was to basically say, ‘Hey, here’s what game music is now. You might be thinking Mario, Donkey Kong, stuff like that. It’s not like that anymore.’ I’m sure the phrase ‘bleeps and bloops’ came up, which is a phrase we in game audio hate,” Schmidt says. “And so the goal was to try to convince them to have a category for game music.”

Although their bid for a new category didn’t immediately pan out, a breakthrough came about the following year when the wording for three GRAMMY award categories was amended with the words “and other visual media” — a vague phrase that was nevertheless intended to encompass video games and other emerging art forms.

“The joke was, ‘Hey, 10 of us lobbied for all this stuff, and best we came up with is adding four words to a category,’” Schmidt says. “But that was when game soundtracks technically could now be eligible.”

From there, it would still be a number of years before video games would have their moment in the spotlight at the GRAMMYs, as the nominated works continued to be dominated by Hollywood film composers. But other breakthroughs eventually came, starting in 2011 when composer Christopher Tin won the GRAMMY for Best Instrumental Arrangement Accompanying Vocalist(s) for his song “Baba Yetu,” originally written and recorded for the 2005 game Civilization IV.

Then, in 2013, Austin Wintory’s soundtrack to the indie game Journey became a finalist in the Best Score Soundtrack for Visual Media category. Despite losing to Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross’ film soundtrack for The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, it marked the first time a video game soundtrack had landed a coveted GRAMMY nomination.

“It was a huge deal. We were super psyched in the industry,” Schmidt says. “It was up against some heavyweight movie scores.”

Perhaps less known, another milestone happened in 2022 when the 8-Bit Big Band won a GRAMMY for their instrumental arrangement of the song “Meta Knight’s Revenge,” which had originally appeared on the Super Nintendo game Kirby Super Star.

“So that was another way where games were sort of sneaking into the GRAMMYs,” Schmidt says.

Finally, in June 2022, the Recording Academy officially laid out the red carpet for game composers with the announcement of a new GRAMMY award category specifically for video game score soundtracks. But for Schmidt and his colleagues, there was still work to be done.

“We had a bit of a conundrum,” Schmidt says.

In order to submit one’s work to the GRAMMYs, an artist or performer has to be a member of the Recording Academy. Alternatively, Schmidt says, a record label can submit a piece of music on the artist’s behalf. In order to become a Recording Academy member, however, an artist must apply via a strict vetting and nomination process that only occurs during the winter and early spring — a window that had already passed by the time the new award category was announced.

“We had this catch-22 where game composers suddenly knew, ‘Hey, I worked on a game this year, and I was going to release the soundtrack, or I already did. But I can’t submit to the GRAMMYs, because I’m not a member. And I can’t become a member, because it’s not the membership window,’” Schmidt explains. “And so that’s where our organization got involved.”

In order to help ensure a healthy number of GRAMMY submissions for the first year of the new award, Schmidt and his colleagues at G.A.N.G. went quickly to work using their various communication channels to get the word out to eligible composers. Not only that, after reaching out to their contacts at the Recording Academy, the two organizations agreed upon an arrangement whereby G.A.N.G. would be allowed to submit game soundtracks for non-Recording Academy members.

“They actually allowed us to submit as if we were a record label,” Schmidt says. “And we ended up submitting a pretty significant percentage of the game soundtracks with this sort of indirect mechanism.”

As it turned out, there was one additional perk that came with being attached to an official nominating body of the Recording Academy, as Schmidt found out he was eligible to attend the official GRAMMY awards ceremony in Los Angeles.

“I wasn’t sure I’d be able to go. And when I found out I was actually eligible to buy tickets, my wife was like, ‘Yes, you’re getting tickets,’” Schmidt says. “So, yeah, I bought a new tux. My old tux was really looking its age.”

Attending the GRAMMYs, he says, was an all-day event — in part because there are two separate ceremonies. The first ceremony, held in a theater from noon to 4 p.m., hosted the non-televised portion of the awards show. That was the ceremony in which Economou accepted the inaugural game soundtrack award.

“Randy Rainbow was the host of the earlier show, so that was fun,” he says.

After the first ceremony, he says, it was a mass migration across the street to the Crytpo.com Arena.

“That’s where the televised show is, and that went from 5 to 9,” Schmidt says. “The only food is what they have in the stadium. And so you have all these people dressed to the nines in beautiful gowns and tuxedos trying not to get nacho cheese on their tuxedo shirts, just trying to get some food between the two shows.”

It was fun to get dressed up and just see what the whole experience was like.

Not surprisingly, both ceremonies featured memorable live performances.

“Stevie Wonder performed and Brandi Carlisle performed. Just amazing music,” Schmidt says. “It was a long day, but it was fun to get dressed up and just see what the whole experience was like.”

If there was still any question whether game music is a big deal, there’s more evidence than just the GRAMMYs. You could also point to the untold hours of video game music — spanning every conceivable genre — being pressed to vinyl, covered by professional musicians, or streamed on platforms like Spotify. It’s all validating for industry veterans like Brian Schmidt who have long understood better than anyone what the “power of game music” truly represents.

“It is nice seeing the recognition,” he says. “Those of us in games can never forget Roger Ebert’s quote that games can never be art. And I love Roger Ebert. I lived in Chicago. But every little bit we can chip away at that, I think, is a positive thing.”