Matthew Picioccio, senior lecturer in DigiPen’s Department of Game Software Design and Production, has been playing and developing games since he was just a little kid. “I made little role-playing and adventure games written in assembly and BASIC on my Apple II,” Picioccio says of his earliest creations. Fittingly, after earning his computer science degree in 2001, Picioccio would start off his career as a programmer on two of the biggest role-playing adventure games ever made at the time — Bethesda Game Studios’ classics The Elder Scrolls III: Morrowind and The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion.

“Back then, we were a little bit more involved in the actual design and implementation of systems ourselves as programmers, something that’s gone away in the industry more recently as games have grown larger and more complex,” Picioccio says. Because of that, Picioccio contributed to a wide range of features on Morrowind, including working with artists to create the sky and weather systems, developing the magic system and all of its effects, and adapting the game to the then-new Xbox console. On Oblivion, Picioccio also worked on many systems, including character facial systems and procedural generation. He also implemented one of the first uses of SpeedTree — a vegetation programming and modeling software that would become a game and film industry standard, used most recently in titles like Ghost of Tsushima and Avengers: Infinity War.

Picioccio followed that up with work on DirectX, XNA Game Studio, Xbox, Kinect, and other technologies at Microsoft. He’s also worked as an engineering leader at companies like Groundspeak, Glu Mobile, and most recently at Microsoft on the upcoming Halo: Infinite, where he contributed to the game’s campaign mode.

Although his nearly 20 years of game industry experience more than qualified him to teach software engineering and programming, Picioccio actually ended up becoming a DigiPen lecturer in 2016 thanks in part to his singing skills.

“I had been into chorus and musical theater in high school and college, and then I got really busy with my career,” Picioccio says. “When I finally managed to carve out some time for it again, I joined a local barbershop chorus and got involved in competing with them.” Through those competions, Picioccio ended up meeting and bonding with DigiPen Associate Dean and Principal Lecturer Jen Sward, a fellow game industry veteran who happened to compete on the women’s side of the same local barbershop scene. “I remember talking to her one day saying, ‘I’d love to guest lecture at DigiPen,’ and her saying, ‘You know, I can do you one better than guest lecturing — we’re actually looking to hire somebody right now!’”

It’s a role Picioccio has grown to love. “The moment when students say, ‘Oh, I get it!’ and I can see how I’ve changed the way they think about making this kind of gameplay system, or how they understand something like network programming — that’s incredibly rewarding,” Picioccio says.

According to Picioccio, software engineering is a discipline of creative problem solving. “Your job, as a programmer, is to craft the simplest possible solution to the problem at hand,” Picioccio says. “While that may sound straightforward, this discipline involves many skills and techniques that take years to develop and master.” With that in mind, we asked Picioccio to share a sampling of five games that give players the chance to practice some of those skills in a fun and engaging way.

Here’s what he had to say, in his own words.

MHRD

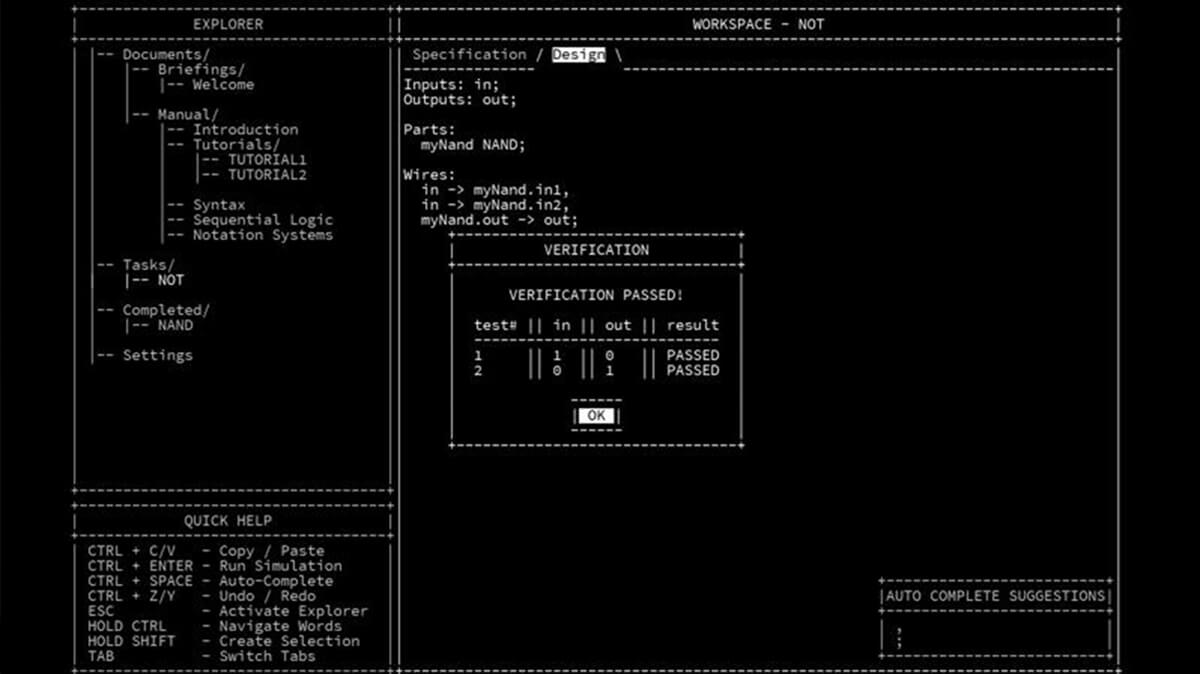

MHRD is a puzzle game based on discrete logic with AND, OR, and NOT gates, and it strongly resembles the classes I took in college many years ago, as well as games from my youth like Rocky’s Boots and Robot Odyssey from The Learning Company.

MHRD is a puzzle game based on discrete logic with AND, OR, and NOT gates, and it strongly resembles the classes I took in college many years ago, as well as games from my youth like Rocky’s Boots and Robot Odyssey from The Learning Company.

The game’s use of logic gates teaches software engineers about binary math and the underpinning of how computers work. The structure of the puzzles also teach the player about modular programming without relying on a specific programming language — utilizing prior puzzle solutions as the building blocks for more complex puzzles.

hackmud

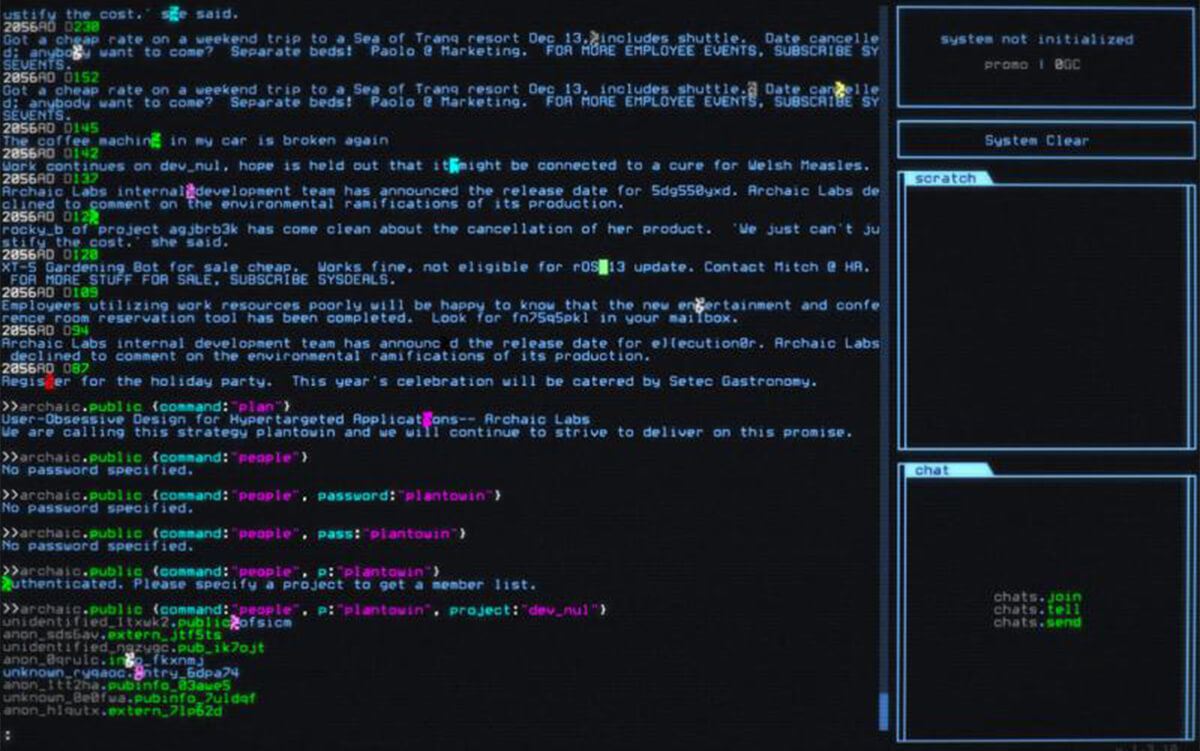

hackmud is a very unique MMO, presented as a graphical chat interface. Players interact with NPCs and other players to gain resources through using existing scripts, and later, writing their own using JavaScript.

hackmud is a very unique MMO, presented as a graphical chat interface. Players interact with NPCs and other players to gain resources through using existing scripts, and later, writing their own using JavaScript.

In hackmud, players slowly transition from being a user — calling the game’s pre-provided scripts — to being a developer, requiring an increasing level of awareness of how the game itself operates. One of the most important skills of successful software engineers is understanding the layer of abstraction you rely upon, even if you don’t program at that level often — something this game makes you aware of. hackmud also teaches the player important lessons about network security and trust — carefully delineating what it means to provide access to certain aspects of your system and raising the player’s awareness of their own security.

Omega

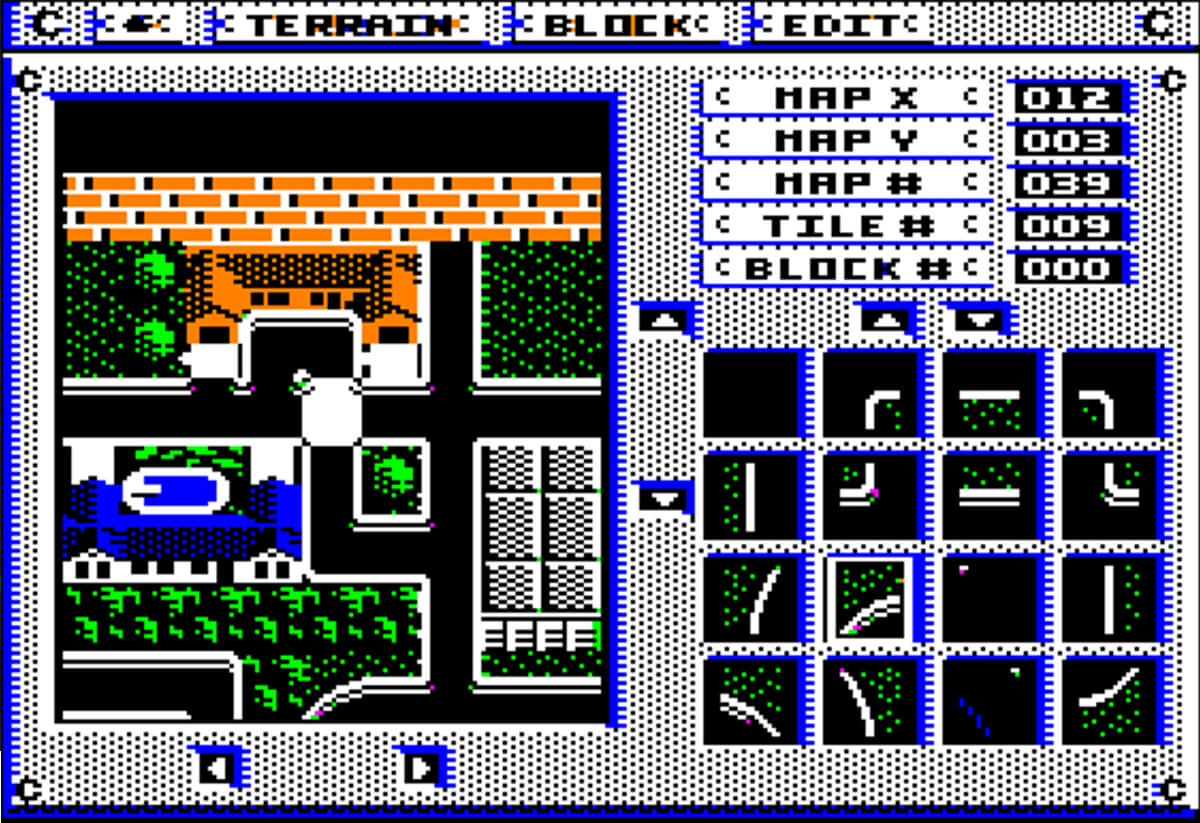

Omega was a groundbreaking game published by Origin back in 1989. It included a complex user interface and a BASIC-like programming language, which you used to program tanks to battle in arenas. Omega was also one of the first commercial games to use a modem for cross-platform play!

Omega was a groundbreaking game published by Origin back in 1989. It included a complex user interface and a BASIC-like programming language, which you used to program tanks to battle in arenas. Omega was also one of the first commercial games to use a modem for cross-platform play!

As a programmer, Omega asks you to manage increases in feature scope. Through “license” upgrades, the game encourages you to refactor your code to incorporate new sensors and weapons, re-evaluating what makes your tank successful in combat. You also must utilize complex technical documentation, learning how to find the information you need to achieve your goals.

7 Billion Humans

7 Billion Humans is Tomorrow Corporation’s follow-up to Human Resource Machine, and both games utilize a simple programming language to achieve increasingly complex goals in a two-dimensional grid.

7 Billion Humans is Tomorrow Corporation’s follow-up to Human Resource Machine, and both games utilize a simple programming language to achieve increasingly complex goals in a two-dimensional grid.

The major innovation of the puzzles in 7 Billion Humans is parallelization, the simultaneous execution of code by multiple characters at once. In fact, it’s the same code each time, though executed by characters at different locations on the map. Throughout the game, the player learns how to write logic that is consistent but sensitive to local state. Parallel code execution is very hard to visualize, and 7 Billion Humans provides excellent experience in an approachable format. The game also encourages players to optimize, rewarding the player for finding shorter and/or faster solutions.

TIS-100

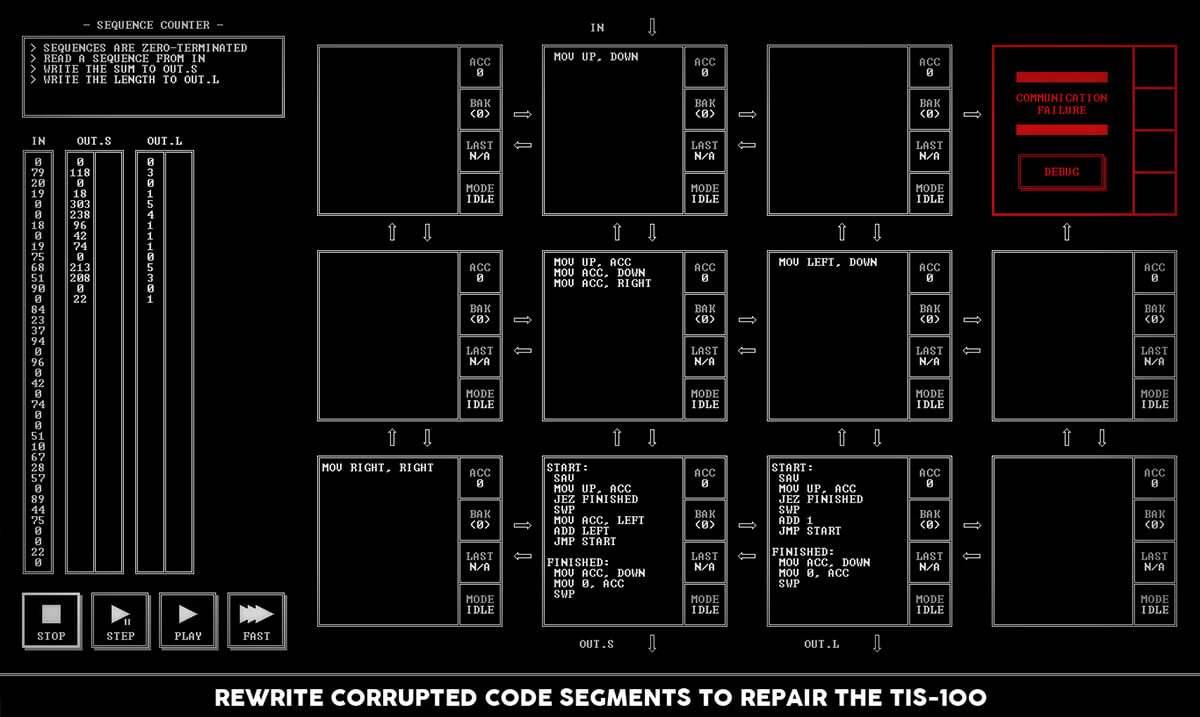

TIS-100 is one of several brilliant games from Zachtronics, but it’s the one that speaks most directly to me. I grew up programming on an Apple II with a very similar assembly language. What TIS-100 adds is the concept of parallel execution of distinct nodes.

TIS-100 is one of several brilliant games from Zachtronics, but it’s the one that speaks most directly to me. I grew up programming on an Apple II with a very similar assembly language. What TIS-100 adds is the concept of parallel execution of distinct nodes.

TIS-100’s fiendishly clever puzzles focus your attention on data flows, more than the code itself and the outside effect of your system. Each node has a small amount of storage and communicates with other nodes through a very small window. While modern systems don’t use this kind of assembly programming, understanding complex data flows and synchronization is key to the distributed data systems that power the websites we rely on like Facebook, Twitter, and Google. TIS-100 also encourages optimization through leaderboards, and it contains some wonderful technical documentation. Once you’ve completed TIS-100, you should also play Zachtronics’ other brilliant puzzle games, including EXAPUNKS, SHENZHEN I/O, Infinifactory, and SpaceChem.

Beyond these games, Picioccio often recommends coding kata sites like CodinGame to those who want to get a sense of what it’s like to solve problems as a professional engineer, as well as practice for programming interviews.